“Ursula was everything you’d expect her to be: biting wit, wasn’t going to suffer fools at all,” artist Charles Vess told me over the phone from his studio in Abingdon, Virginia. Vess, a long-time Ursula K. Le Guin fan, was chosen by Saga Press to illustrate their collection of Le Guin’s famous epic fantasy, The Books of Earthsea, a massive tome comprised of five novels and various pieces of short fiction. When speaking with Vess about the project, his passion for Le Guin’s work and his intimate experience with Earthsea was obvious.

Le Guin’s Earthsea is one of fantasy’s most seminal works. Published in 1968, amid the vacuum left behind by the massive success of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, A Wizard of Earthsea was joined a couple of years later by Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni Rising as the vanguard of a resurgent genre. I will allow my fellow Tor.com writers to extoll the virtues of Earthsea, except to say that the ripples of its influence are still impacting many of the genre’s most successful and popular novels, including Patrick Rothfuss’s immensely popular The Name of the Wind. Le Guin’s impact on fantasy cannot be overstated (and that’s to say nothing of her brilliant science fiction, like The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, which similarly influenced that genre.)

Vess had an opportunity to meet Le Guin long before he became involved in The Books of Earthsea, when he considered himself simply a fan of her work. It was at a convention in Madison, Wisconsin—perhaps WisCon or the World Fantasy Convention, he couldn’t quite remember—when he found himself at a gathering with Le Guin. “I couldn’t bring myself to go talk to her,” he told me with his deep-hearted laugh.

“What was I going to say? ‘Gee, you write good?’” He laughed again.

“So, I didn’t. I watched her from afar. My wife went and talked to her, got some books signed.”

This was, perhaps, in 1996, when Le Guin was the Guest of Honor at WisCon. Little did Vess know that many years later, he would collaborate with Le Guin on a volume that would put a ribbon on over 40 years of Earthsea, a final gift to new and longstanding fans of the wondrous series. Le Guin passed away in January, 2018—ten months before the collection was released, but not before she spent four years collaborating with Vess to bring her world to life one last time.

Vess first encountered Le Guin’s work in 1970 when he read A Wizard of Earthsea for a college children’s literature course. “I fell in love with it—so much so that I looked around for her other books, and liked those as well.”

Since then, he’s read “loads of her work.” So, when Joe Monti, Editorial Director of Saga Press came calling, asking Vess if he would like to collaborate with Le Guin on a high-end collection of her work, Vess responded with both excitement and nervousness.”I was really flattered and intimidated and excited. Then Joe said to me, ‘Well, Ursula said she has to like whoever’s going to work on this book with her. So, you have to call her up and talk to her.’ I was like, ‘Oh, god. Here we go!’”

“I shouldn’t have worried, though. It was a great conversation that lasted over an hour. We left off agreeing that we wanted to collaborate.”

Le Guin had enjoyed previous collaborations with theatre groups and musical artists, but told Vess that every artist she’d worked with previously would say, “Yes! I’d love to collaborate,” and then that was the last she’d hear from them until the book was finished and printed. “So, I don’t think she believed me when I said I wanted to collaborate. But, after four years and lord knows how many emails, she sent me a copy of her latest book, her essay book, and her dedication to me was ‘To Charles, the best collaborator ever.’”

There was perhaps a bittersweet note to Vess’s laugh.

“I felt very gratified. It was a long, and very intimidating project, but it’s the best kind of project to have, because it will bring out the best in you.”

Vess describes himself as a book lover and a collector of old, illustrated books. “One of the few joys of getting older is rereading a book and bringing a whole new experience to it,” he said. “You can grow along with the books.

“As a reader, I have a very different experience reading the books now than when I was younger.” He loved A Wizard of Earthsea when he first discovered it, but, he admits, bounced off the second book, The Tombs of Atuan, as a twenty year old. “It didn’t have enough dragons,” he said with a laugh. “Not enough obvious adventure. But now when I read it, in my sixties, it’s a very meaningful book. I love it.”

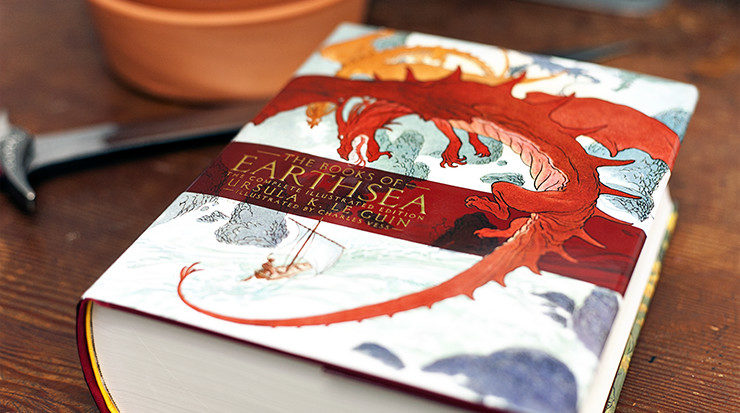

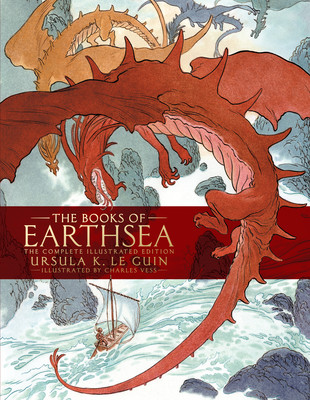

As a collector and lover of books, Vess said that this project was particularly fun and rewarding. “It’s a beautiful book,” he said. “And way bigger than anything you’re imagining. It’s eleven pounds!”

Ursula’s stories were long since written and finished when work began on The Books of Earthsea, but she spent those four years working with Vess to get the illustrations just right.

“I’d pretty much reconciled myself to drawing what she was looking at in her brain,” Vess said when I asked whether it was difficult to separate his vision for the story, which had percolated in his head since the ’70s, with hers (which had existed for much longer, of course.) “I had no problem with that. She’s particularly brilliant. I really wanted to let her see the world that was in her mind. I tried really hard to do that. That was part of our collaboration. The writer and the artist sort of become a third entity. You become something better than you are as yourself. Aesthetically better. Not morally better.” He laughed. “Aesthetically better.”

Vess counts Alfred Bestall, Terri Windling, and Arthur Rackham among his greatest influences, but over the course of his career, which began in the ’80s, he has established himself as one of our most critically acclaimed and recognizable fantasy artists. His lush pen and ink drawings have given life to the works of visionary authors like Neil Gaiman and Charles de Lint—evocative and magical, like something drawn from a world more magical than ours. You know a Vess immediately when you see it, and that is, perhaps, the greatest compliment one can pay an artist.

The Books of Earthsea is a coming together of two of fantasy’s most lauded talents. What was it like for Vess to work on a series that has reached legendary status among its community of fans?

“I was aware of all that, but, really the person I was trying to please was Ursula,” he said. “Trying to draw the world the way she saw it.”

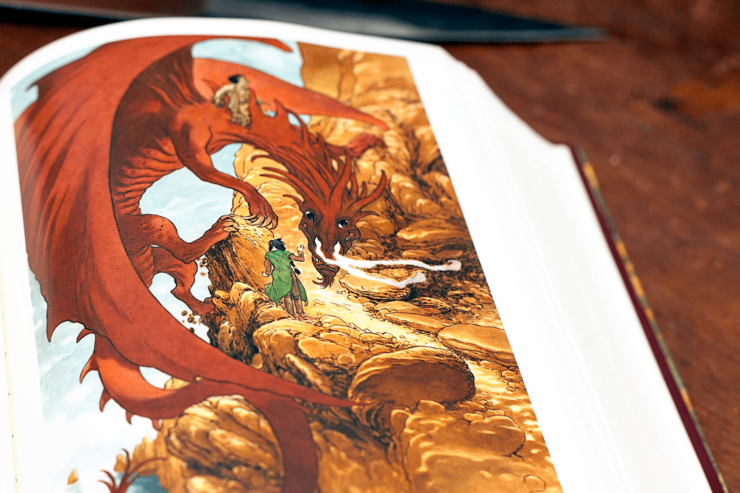

The book required a lot of effort from Joe Monti as he navigated a complex contractual labyrinth requiring sign-off from three separate publishers. Vess said it took almost a year to get things sorted, but in the meantime, he and Le Guin got to work. “I didn’t illustrate the book during that year, but Ursula and I went back and forth on what her dragons looked like. It was a luxury. We didn’t have, like, a week to figure out what the dragons looked like. We had a long time, and could go back and forth. We kept refining our ideas. Eventually I arrived at a drawing she was very happy with. That’s what I wanted. For her to be happy.”

One of the major themes that came up time and again during our conversation was that of collaboration. Vess spoke fondly of the relationship he developed with Le Guin, and also Monti’s leadership and vision.

“I’ve known Joe, oh, at least twenty years,” Vess said. He went to bat for Monti when Ursula showed some reservation about the project. She’d had some prior dealings with Simon & Schuster (Saga Press is an imprint of S&S) that had left her with a sour taste, and that affected her expectations for The Books of Earthsea. “‘Well, this is different,’ I said, ‘because Joe Monti is, among many other things, a very moral person. He wants to make a beautiful book.’”

“She went, ‘Well, I’ll wait and see.’”

“And, he did!” Vess said with a laugh.

“Joe searched out everything possible. This book is really an amazing compendium of Earthsea. One of the decisions he made in the beginning was that he was going to leave Ursula and me alone to do the interiors. ‘Except the cover,’ he told us. ‘The president of the company will have to look at it, marketing will have to look at it, things will happen with the cover, but the interior is up to you guys.’ So, Ursula became my art director. That was a really amazing vote of confidence in myself.

“I showed everything to Joe as it went along, but he rarely, if ever, made any comments.”

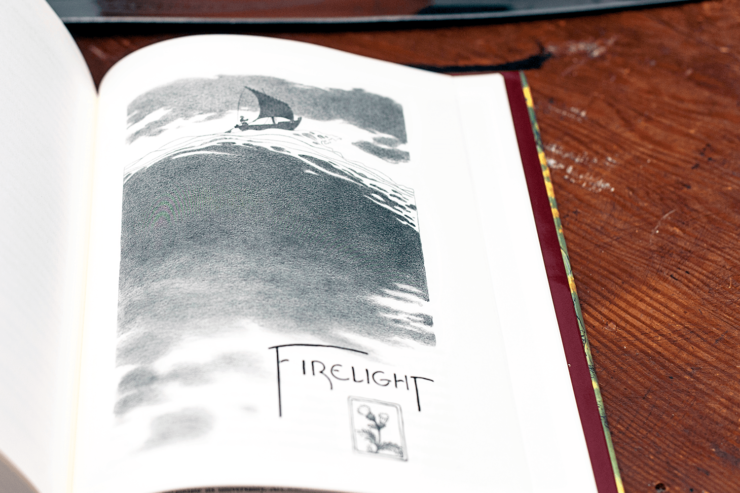

Sadly, Le Guin passed before she could see the final product. However, she worked on, refined, and approved every image in the book alongside Vess. Except for one. “It was only the very last story that they found in papers after she’d passed that she didn’t approve or look at what I drew,” Vess recounted. “Beautiful story. It made me cry when I read it.”

That must have been a powerful, bittersweet moment for you, after working so long alongside Le Guin, I said.

“It was. I’d spent four years on the book. I was done. It took a couple weeks for me to get my head around the fact that I was done. Then I started working on this other book project that I’d put to the side while I worked on Earthsea.

“And then Joe called me up, and said, ‘Well, I have some good news and bad news. We found this story, and we want it in the book. But, we really want you to illustrate it.’

Buy the Book

The Books of Earthsea

“I’d sort of made my formal goodbye to the book, and then here was this other story. He sent it to me, and I read it. Teared up. Then it was, ‘How do I make an illustration as evocative and poetic as the story?’ I probably did about twelve sketches for myself, honing the idea down. I ended up with a piece I was very happy with.”

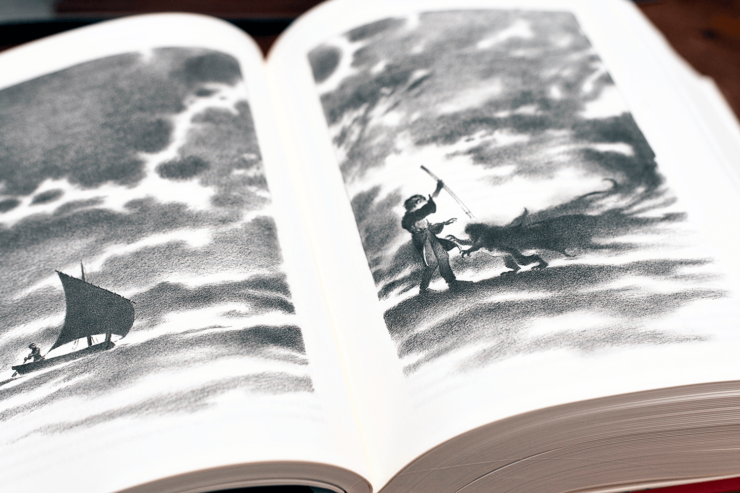

The story is “Firelight,” and the illustration, above, of a lone sailor silhouetted against a large, surging sea, could, perhaps, also be interpreted as a final farewell to Le Guin as she sails off into a better world than this one.

Working in such an organic and collaborative method was freeing for both Vess and Le Guin.

“Ursula spent so many years arguing with marketing departments. She envisioned Earthsea as a world mostly comprised of people of colour. It wasn’t just black people, but also Mediterranean or Native American people. All sorts of shades of brown. No one ever put that on a cover. She’d had a lot of fights about that. So, this was an opportunity to gird for battle—to make the book [and the world] look the way she’d always envisioned it.

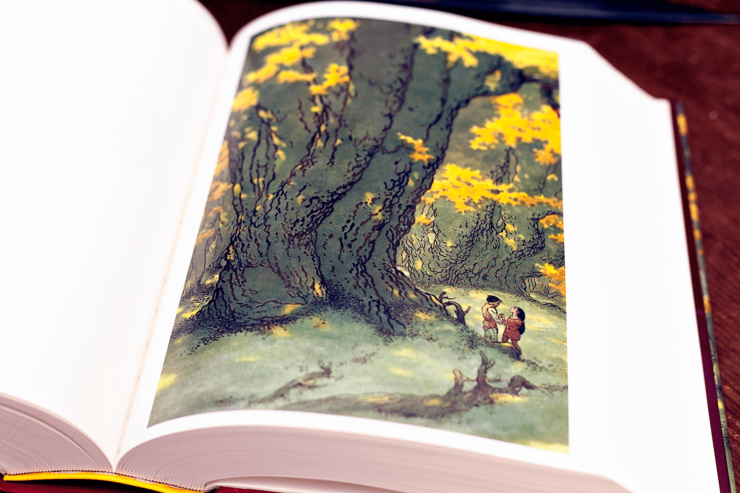

“Millions of people have read [Earthsea], and they all have their own idea of what Ged, Tenar, and all the other characters look like. So, I wanted to pull back. I didn’t want to do portraits. I wanted to focus on the environment, the landscape, the poetry of where they were. Ursula was quite happy about that.

“I would send her sketches, and she might remember something that she hadn’t thought about in forty years, and start telling me a story. Wild stories about how she came up with some of these ideas.” For Vess, who was a fan first, collaborator second, it was a “fascinating experience” to peek inside Le Guin’s mind as she recalled how she created the world he loved so much.

One of Vess’s favourite scenes to illustrate comes at the end of the first volume, A Wizard of Earthsea. Ged is far out at sea, finally confronting the shadow creature that has haunted him for much of the book. “I had this drawing, and the shadow creature obviously had a head and arms,” Vess describes. “Ursula responded, ‘Well, it’s a little too human-like.’

“She started telling me this story. Back when she was writing the book, to relax, she would go out in her garden and put things onto a little glass slide, to look at under a microscope, and watch what happened,” Vess recounted, becoming lost in his memory of the conversation. He suddenly laughed. “Which is odd enough.”

One day while doing this, Le Guin saw a “very creepy, dark” something moving across the slide. “That became her shadow,” Vess said.

In their open and collaborative manner, Le Guin responded to Vess’s illustration by sending him a copy of the story, and a microphotograph of a microscopic water-borne creature called a tardigrade. She couldn’t see it with that level of detail at the time, but the image of the mysterious creature stayed with her, and Vess was able to implement elements of the tardigrade’s silhouette into his final illustration, perfecting Le Guin’s shadow. “It was really fascinating to hear that story, and it of course changed my whole drawing once I’d heard it.”

I’d always pictured the shadow as a humanoid reflection of Ged, a projection of his darker self, I admitted to Vess.

“Me, too,” he said. “But her description is different than that, and her explanation of it was way different than that.”

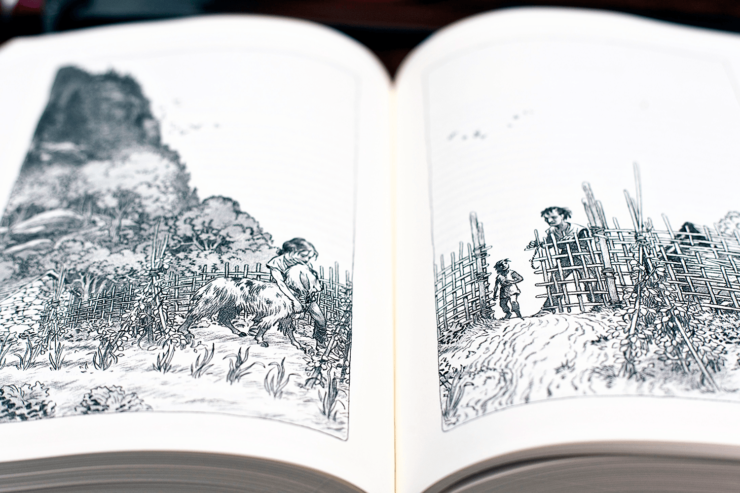

Le Guin had a very strong idea of what her world and story were about, and Vess was eager to help her realize her vision. “One of the things we talked about a lot was that most epic fantasies are full of marble halls, great kings, queens, and lordly wizards wandering them. Ursula didn’t want that. She didn’t write the books that way. She wanted it to be about people living on the land, and tilling the soil.”

One of the book’s double-page illustrations shows Tenar, Ged, and Tehanu after they have just caught a goat that escaped its pen and fled into a garden. “It’s a very quiet drawing.” Le Guin loved it. “Every once in a while, she’d go, ‘More goats, Charles. Put more goats in there.’”

“So, I did!” he laughed.

Aidan Moher is the Hugo Award-winning founder of A Dribble of Ink, author of “Youngblood,” “The Dinosaur Graveyard,” and “The Penelope Qingdom,” and a regular contributor to Tor.com and the Barnes & Noble SF&F Blog. Aidan lives on Vancouver Island with his wife and kids, but you can most easily find him on Twitter @adribbleofink and Patreon.